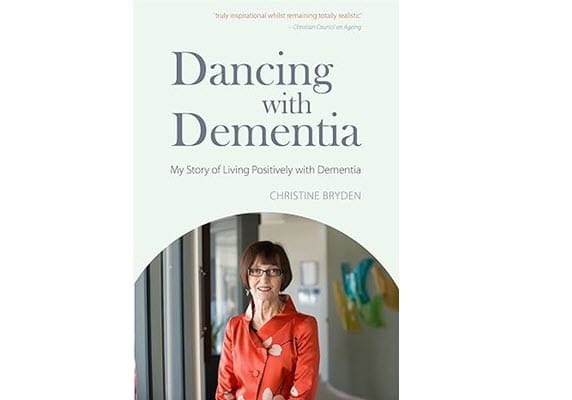

Dancing with Dementia

This is a book review I wrote several years ago, and the science has of course moved on, but it is still an interesting story. Also note that several other books have the same title.

I have an unusual response to this book, for a couple reasons, some of which have to do with my own family experience and some which come from the questioning that my scientific training demands. The author, Christine Bryden, has been diagnosed with dementia, from a full battery of tests that include brain scans, cognitive tests, and so on. She notes a number of alarming memory symptoms. Her doctors are convinced she has dementia, and they remind her of that frequently.

Here's the thing, though. Bryden gets somewhat better (her doc is reluctant, but eventually believes her). The dementia seems to come and go, and in fact she has been improving or at least steady for awhile, to the extent that she even went back to driving after a hiatus. I don't recall her mentioning what type of dementia she has, but she's had it for many years, so here's my first question: does she really have dementia or some other, more treatable neurological condition?

Let me tell you what dementia looks like to me. My mother died of it, and it wasn't pretty - a steadily downhill slide that went from minor forgetfulness to the inability to recognize her own children; from taking care of herself to incontinence to the inability to even know why she was wet; from active to wheelchair-bound to bedridden and comatose. Now I understand that there are multiple types of dementia - the beloved fantasy author Terry Pratchett died of a type different from Mom's - but I didn't know of any that might go into remission. Is Bryden's illness the latter and how common is it?

Bryden attributes her improvement to prayers from her church and to God, but if that worked, Mom would still be here - she was an active and unflagging Christian, too, and it didn't help. A better way to look at the church angle is to suggest that some people (Bryden) may be better able to refute the psychological pressure from the medical profession to "be sick" by utilizing the counterweight of prayer. If that's the case, if the severity of the condition maps closely to the intensity of patient hopelessness - how can we exert similar counterpressure in more and different ways? (I get a newsletter from Harvard Medical School that recommends physical exercise, continuous learning, socialization, proper diet, and lowered stress, among others).

After all, dementia is still after all this time not a well-understood set of conditions. Some of the "diagnostic tests" are laughable in their crudity: parlor games like "can you remember five words fifteen minutes later" and sniff tests such as "how close to the jar do you have to be to smell the peanut butter." (I'm not making this up. Google it.) There is even a contingent of dementia researchers who are questioning whether current science is looking at the correct problem. Are tangles found on brain scans indicative of the condition - some people with such tangles have no other symptoms at all - or just an immune response to something else?

Bryden does include some excellent insight into what it's like to have such a condition, and the book is worth a read for that even without answers to these questions.

Recommended.

I received a free copy of this book from NetGalley in exchange for a review. The image above is from the book's Amazon page.

--Gail